In her 2019 master’s thesis at Tufts Urban & Environmental Policy & Planning, Lily Ko assessed the equity implications of the MBTA’s new fare collection system (AFC 2.0), produced a method to prioritize placement of fare vending machines for affected riders, and provides take-aways from how other transit agencies made the switch to all-doors boarding and cashless models (meant to improve the efficiency of the system).

As the new system will no longer allow cash payments onboard buses and trains, she explained that the most affected will be riders with lower income who may be un/underbanked, riders who are lacking smartphones or unable to keep up with technological changes (such as the elderly) and riders who use early morning or late night service when retailers that top up (or reload) Charlie Cards are closed.

Ko found that in 2018, riders paid cash for almost 9% of all boardings and that 12% of stops accounted for 75% of all cash boardings, with high concentrations in lower income communities and communities of color. The MBTA’s contractor for implementing this new system is not explicitly required to place fare vending machines at stops with the highest cash use and is relying significantly on retailers to provide Charlie Card cash service to stops within a 10-minute walking distance. Cash-dependent riders may have to walk up to 20 minutes round-trip just to top up their cards and may not be able to do so in the early morning and late hours when retailers are closed.

Ko’s study provides a method for the MBTA to prioritize placement of supplemental fare vending machines, based on analysis of MBTA ridership and payment data and using criteria generated from qualitative feedback from community advocates. Based on research of other transit systems that also switched to all-doors boarding and/or cashless models, Ko recommends that the MBTA assess the savings from going cashless and reinvest those savings to support cash-dependent riders and to collect more feedback from vulnerable riders and mitigate impacts through a more gradual phase-in of the new system.

The work to produce a method to prioritize placement of supplemental fare vending machines was conducted as part of Ko’s internship at the MBTA from October 2018 to August 2019. Read on below for more details of the study.

Who will be impacted by the change to the new fare payment system?

The Massachusetts Bay Transit Authority (MBTA), the state agency that provides Greater Boston’s public transportation services, will be implementing a new fare payment system (Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority [MBTA], 2019) within the next few years. Automated Fare Collection 2.0 (AFC2) will bring benefits for the vast majority of riders, including more convenient payment and improved service speeds.

The MBTA plans to accomplish this by moving to an all-doors boarding and cashless model—which means that the onboard fareboxes will be removed and riders will no longer be able to pay the fare directly with cash or top-up (reload) their Charlie Card (fare card) on-board. Customers will be expected to top-up their Charlie Cards before boarding. This change will not be a problem for most riders as one of the new payment methods will include a phone app allowing customers to top-up their cards using a debit or credit card.

The AFC2 farebox removal is mainly an equity issue that will significantly affect:

- people with low income who need to top-up their Charlie Card frequently because they do not have enough money to top up large amounts at once—particularly unbanked and underbanked populations who do not have access to a debit or credit card and a smartphone with internet access;

- people who are slow to adapt to technological changes, such as seniors;

- people who are physically or psychologically unable to adopt the necessary changes, such as people with disabilities; and

- people who utilize early morning or late night MBTA service during hours when retailers—where people can top-up their Charlie Cards—are closed.

In this case, transit equity is about accommodating these riders with fewer options to access a point-of-sale (POS) due to barriers. The 2017 survey on unbanked and underbanked households by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) and the U.S. Census Bureau showed that 6.5% of U.S. households were unbanked and 18.7% of U.S. households were underbanked (Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation [FDIC], 2018).

However, there are demographic divides as unbanked and underbanked rates were higher among lower-income, less-educated, younger, black, Hispanic, and working-age disabled households, as well as households with volatile income (FDIC, 2018).

As for the digital divide, the Pew Research Center found that higher income, White, and younger people are more likely to have a smartphone than lower-income, Black or Hispanic, and older people (Rainie, 2017). Furthermore, disabled Americans are less likely to use technology, less comfortable with the internet, and spend less time online than those without a disability–and the population is disproportionately made up of seniors, an age group with a lower level of digital adoption than the nation as a whole (Anderson & Perrin, 2017).

These are the demographics of riders that may be paying more in cash on-board MBTA vehicles and at a higher risk of being negatively affected by the AFC2 changes.

So, how large of an issue will this AFC2 change be?

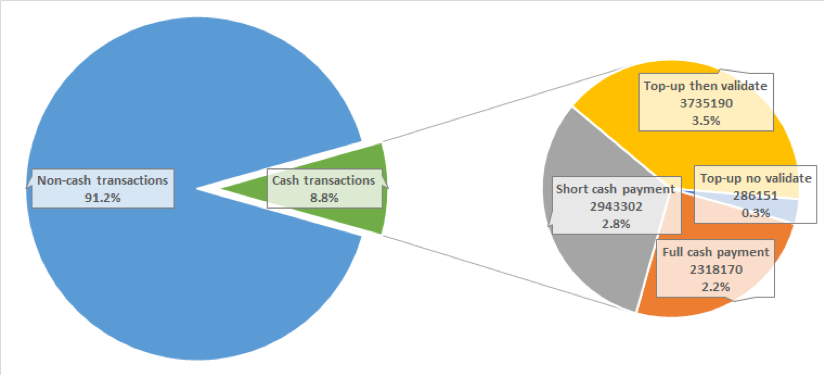

Out of the nearly 8,000 stops in the MBTA system, over 95% of them are farebox stops where riders are currently able to pay in cash or top-up their card on-board (including all bus stops and Mattapan Trolley stops, and a portion of Green Line and Silver Line stops). Out of 105,927,074 total farebox boardings in fiscal year 2018, 8.8% were farebox cash boardings (or transactions)–accounting for 9,282,813 boardings. The chart below demonstrates this and the breakdown of farebox cash transactions into different types.

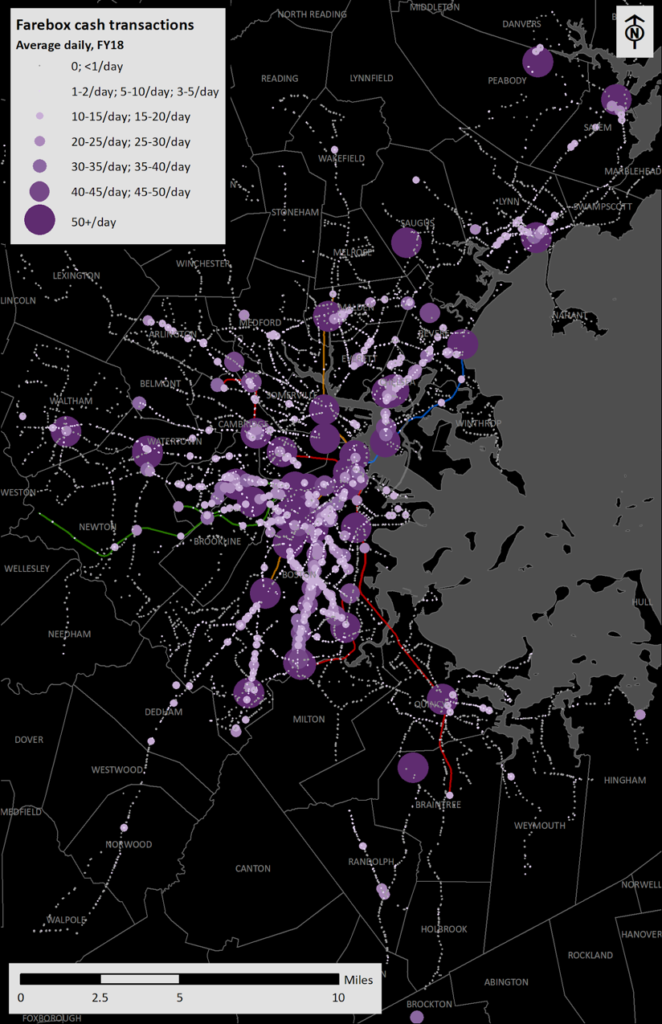

Some stops have significantly more cash boardings, averaging more than 50 per day, while many other stops have an average of less than one cash boarding per day. See the map below for the distribution of FY18 farebox cash boardings. Out of all farebox stops in the system in FY18, 12% of the stops covered nearly 75% of the farebox cash transactions.

Equity implications of contract requirements

The AFC2 public-private contract will require the point-of-sale (POS), or fare sales, network to be significantly expanded with many more FVMs and retailers; however, the equity gaps in the contract do not explicitly account for the most vulnerable riders. Taking a critical look at the contract requirements, I found four main equity implications:

- There is no explicit guarantee of farebox stops with high cash usage.

- Basing POS requirements off of numbers of boardings and alightings means that people paying in cash only have half the number of “votes” in the SI’s assessment for decisions to cover a stop (since alightings cannot be inferred without a Charlie Card).

- “Coverage” of a stop with a POS allows locations to be up to 2000 feet or a 10-minute walk away from the stop (or up to 20 minutes roundtrip).

- Early morning and late night riders will not have access to fare sales if their only nearby POS is a retailer.

Method to alleviate the equity issue

The MBTA plans to mitigate the POS network equity issues by providing supplemental FVMs at stops—but have a limited amount of resources with which to do this. My thesis provided one data-driven method to solve this optimization problem: Given AFC2’s farebox removal, what is the best way for the MBTA to fulfill as much of affected, cash-dependent rider needs as possible with supplemental FVMs—with limited supplemental resources?

The method includes a review of data inputs (e.g., the average number of farebox cash boardings per day) considered and chosen, and was strengthened through a focus group with the AFC2 Policy Development Working Group (PDWG)—made up of transportation, climate, and social justice community advocates—using a data gallery walk. It includes different types of coverage principles the MBTA could use (e.g., cover all stops with a daily average of 10 or higher farebox cash boardings), which were then put together into a scenario analysis with 10 options. The analysis presented the number of stops requiring supplemental FVMs and the percent of farebox cash transactions covered for each option.

The final data inputs included total farebox cash transactions, senior/TAP farebox cash transactions, student/youth farebox cash transactions, and “early AM / late PM” (10 P.M. to 6:59 A.M.) farebox cash transactions. After feedback from the AFC2 PDWG, I included two additional variables: 1) comparable ridership levels as modes with guaranteed fare vending machines, and 2) access to FVMs in subway stations during closed hours for early and late bus riders. These data variables were incorporated into the overall methods to prioritize stops for supplemental coverage.

The insights gathered from the data gallery walk and the resultant strengthening of the method presented in the thesis is proof of the value of co-production with the community. Furthermore, I incorporated an Excel script and GIS analysis into the method to use a “reasonable walking distance” principle for people accessing points-of-sale (because 2000 feet from a point-of-sale is too far to reasonably consider a stop “covered”). (It is important to note that this data-driven approach was a starting point for determining the final list of stops to receive supplemental FVMs and is one part of the MBTA’s broader approach that will incorporate community feedback.)

Policies beyond the optimization problem

Given the AFC2 farebox removal, this method provided some strategies for the MBTA to fulfill as much of affected, cash-dependent rider needs as possible with limited resources for supplemental FVMs. Yet—without the political will and proper funding—in no feasible scenario will 100% of farebox cash transactions be covered by a point-of-sale because that would require thousands of FVMs. Thus, other policies that go beyond the optimization problem are required.

The MBTA needs to provide viable and convenient alternatives for its vulnerable riders. The following policy recommendations to accommodate the T’s most vulnerable riders are mostly derived from the review of other transit agencies on all-doors boarding and cashless systems. All-doors boarding and cashless models have been taken up by many transit agencies in the U.S. and abroad. My research into these models (including transit systems covering the cities of San Francisco, Austin, Seattle, Los Angeles, Chicago, Cleveland, Minneapolis-St. Paul, New York City, Washington D.C., Philadelphia, Stockholm, Kigali, Bangkok, and London) resulted in several policy implications for the MBTA regarding their own move to all-doors boarding and cashless.

Most reports on all-doors boardings and cashless systems focus on the reduction in dwell times, fare media (e.g., payment methods, fare card readers), and fare evasion and inspection. Little has been discussed about how agencies set up their fare sales network, including FVMs, retailers, and other fare sales locations. However, it is apparent that recruiting and retaining retailers may be challenging, and that it is important to have a balanced mix of both a national retailer as well as small shops as part of the point-of-sale network. Furthermore, flexibility in fare inspection may help to prevent vulnerable riders from being stranded–and what ‘flexibility’ looks like should be co-produced with community members. The MBTA have already expressed commitment to these policies, but the following findings are additional actions and policies for the MBTA to consider.

First, one major impetus for farebox removal for multiple agencies appeared to be cash savings. For instance, the main motivation for Transport for London (TfL) to discontinue cash payment on-board was significant cost savings and it was reported that $24 million Euros, annually, could be reinvested into the transport network (TfL, 2014). The MBTA has not reported on any potential cash savings and reinvestment back into system improvements. Additionally, if there are savings to be had from going cashless, one way for the MBTA to reinvest back into the system could be through equity-driven initiatives—such as a low-income fare. The move to a cashless system may even be more viable given a low-income fare, which may allow riders to top up their Charlie cards less frequently.

Second, it would be prudent to roll out a cashless model in phases. Most agencies have piloted or are piloting cashless first through a few stops or a few routes/lines. The easiest stops to go cash-free at are busways, where large numbers of farebox cash transactions occur even though there are fare vending machines. Enforcing a cashless model at the busways that are ADA-accessible to the FVMs should speed up service by an appreciable amount. Moreover, like the Metro in D.C., the MBTA could solicit feedback on the change before deciding on a systemwide change. A phased rollout would allow the time for riders to adjust to the change, as well as AFC2 implementers to sufficiently fill out the POS network and make adjustments based on community feedback.

Finally, all-doors boarding and a cashless system are distinct characteristics of any given transit system. Though the models are often used in conjunction when discussed as a way to speed up service by reducing dwell times in AFC2, they are not synonymous. Most U.S. transit agencies that have adopted an all-doors boarding model have not also adopted a cashless model—the agencies continue to allow cash payments through the front door. Where the agencies have gone cashless, they provide FVMs at the stops.

Accessibility to top-up locations has been shown to be a problem. If both all-doors boarding and cashless are truly necessary to decrease dwell times to the desired level for the MBTA and its customers, research should be conducted to demonstrate the individual effectiveness of all-doors boarding and a cashless system at reducing vehicle dwell times—in comparison with their combined effect. Like other agencies, the MBTA should report baseline information to determine the room for operational efficiencies.

The MBTA must exercise due diligence in ensuring that their policies around fare payment are truly inclusive, and it begins with the policies above.