“I firmly believe that crisis cannot be the only driving force behind climate action. We need to incorporate an element of fun. The crisis narrative is a powerful motivator, but it can produce a short-sighted approach to problem-solving. Yes, climate change is a pressing issue. Yes, we need to move forward with action. But it doesn’t have to always be the ambulance at the bottom of the cliff…We need to think about the larger systems we’re operating in and who we will be supporting in the long term. [Serious] games allow people to think about that in a big-picture, holistic way.”

— Kathryn (Kate) Davies, Tufts UEP Faculty Member

Climate change adaptation and mitigation is not often considered a fun activity. In fact, the implications of climate change can make planning for it a deeply personal and painful process. However, UEP Faulty Member Kathryn (Kate) Davies just dropped some new research showing how climate planning can be a more enjoyable and productive process if it were transformed into a game.

Davies’s research was recently published as a chapter in the book Re-Envisioning the Anthropocene Ocean. The chapter “Adaptive and Interactive Futures: Developing “Serious Games” for Coastal Community Engagement and Decision-Making” explored the use of serious games, those intended for purposes beyond pure enjoyment, for climate adaptation and planning in New Zealand. In a recent discussion, Davies shared her experience and research revelations.

Practical Visionaries: Can you provide a brief overview of the chapter and the motivation behind researching the use of serious games in climate adaptation in New Zealand?

Kate Davies: Sure! The chapter is about serious games and their role in climate adaptation, planning, and community education. It explores serious games as a method of helping people understand the implications of climate change and the choices available to communities to mitigate and adapt to changes. We started this work when I was based in New Zealand, working for NIWA, the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research. The needs of local communities very much drove the work. Sea level rise is a very pressing issue in New Zealand. Planners and decision-makers were navigating conflicts with diverse interests about climate mitigation. Trying to get to a place where they could implement something was a really long and painful process, so they came to us for support. Incorporating games in this context helps individuals become more comfortable with an experimentation mindset. It introduces them to this concept without the immediate effects of climate change impacting them personally. It takes some of the pressure off of decision-making. We also found that using games enabled people to have conversations they might not otherwise have. It helps them to move beyond defending their viewpoints and be more receptive to those of others. It goes to a fundamental human approach to problem-solving, which is play. Humans – we’re a curious species. To solve problems, one of the things that we do well is play with things, mess with them, and experiment, and we often come up with creative solutions.

What types of games did you worked on during your time at NIWA?

We experimented with a bunch of different ways to involve people with gaming around climate change. We developed multiple analog games that we would test at big agricultural fairs with huge crowds of people. We’d have a five-minute sea level rise game that people would play with dice and different little plastic models of farms and stuff.

I was loosely involved in creating a multi-day game in collaboration with one of the iwi – that’s the largest social unit recognized by Māori, the Indigenous people of Aotearoa New Zealand. The iwi I worked with aimed to address the issue of flooding their land, particularly of their Marae, the central meeting house space for their community. The game helped them evaluate their options to adapt1.

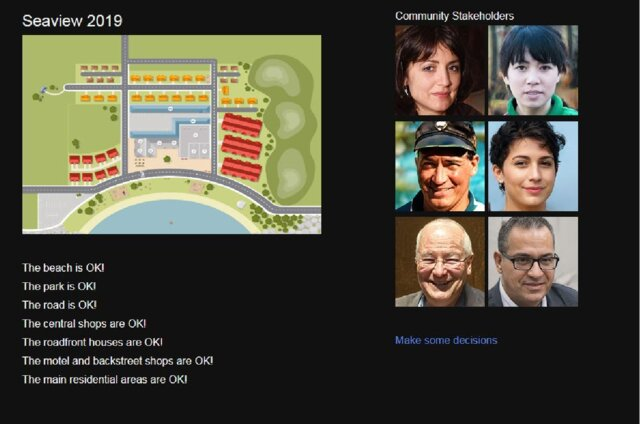

We also developed a computer game called Adaptive Futures, designed more for regional planning organizations. That has been used in a bunch of schools, universities, and different local planning organizations to help them work through conflict with some of the key stakeholders dealing with these issues. It’s really fun. It is a great way to bring people into the space to work through some otherwise stressful stuff. It allows people to envision themselves in many different scenarios. You can take on different roles in the gaming space; you develop empathy for other key players and their decision-making. So it’s a really great tool. I’ve got a link I will send you so you can play the game if you want.

Keep in mind that it was designed for New Zealand. Some of the language and the issues are not necessarily applicable to the American context. The games are currently being developed for very specific contexts. They’re not generalizable. Navigating the issues between specificity and generalizability is a space where the games are not doing a great job yet and where active work is going on.

Could you expand on that tension between specificity and generalizability?

Specificity means that you can really get people to think deeply about the context of their specific decision-making scenario. However, developing a game that works for every context takes a lot of time, energy, and resources, and timing is critical. The games are effective in helping people understand the issues, work through them, confront them, and even socialize them, but we need to deploy them more quickly and in a wider area.

I am working on finding ways to apply fundamental principles of game development to climate change decision-making. I have already collaborated with Prajna [a second-year UEP graduate student] on a literature review to explore potential solutions. Our goal is to create faster game development methods that can be easily adapted to different communities and situations while incorporating a central game model.

What do you mean by ‘socializing these issues’ and why that is important?

People are generally willing to engage with the idea that climate change is happening and that we need to address it, but ‘managed retreat’ is a dirty word. No one wants to talk about it as a real possibility. It’s just so fraught for people. It’s so personal. Going back to this Marae that we worked with – this community has lived on that particular piece of land for generations. It is their homeland, and the idea that they would leave that land voluntarily before it fell into the sea or was completely flooded out is uncomfortable. I don’t think anybody else can or should make that decision for them, but people need to start thinking about the possibility of options like managed retreat, or they will limit their choices upfront. Through gaming, there’s an opportunity to give people some exposure to it. Take some of the sting out of some of these terms and ideas so that managed retreat can be less of a dirty word and more of a tool in people’s toolkits.

Would you say you saw a pattern of people putting their heads in the sand and pretending that managed retreat doesn’t exist?

Definitely. This response is one of the reasons we developed the computer game. Gaming shows you that sometimes what you think of as a far-off event could happen here and now, and you need to start planning for it now. Otherwise, you won’t have the money or the resources. You won’t have done the socializing work you need to do. We have survey data from people who played [Adaptive Futures] over and over again, where their risk matrix was a toss of the dice as to whether or not you’re going to have a major flooding event. People said their biggest takeaway was the realization that climate-related disasters are not something that will happen way off in the future but something that could happen right now, and we have to plan for it now.

Who participated in the surveys? What groups of people would be the best target candidates for playing serious games in other communities?

Great question. We tested it mostly with students, often in environmental management-type classes. Those were our test audience, but we also tried it with planners, policymakers, and decision-makers working in regional planning. So this is equivalent to state-level planning organizations. But different games can be developed for different audiences. You certainly get a lot of value from using serious games with any age of students.

What would you say the main message is that you were hoping to convey while designing the games?

The goal is for players to walk away with a firm understanding of the implications of climate change, the urgency to plan for it, and their available options to respond to possible threats. Through gameplay, players learn the advantages and drawbacks of each choice and need to reconcile disputes. If you want to build a giant seawall, it will protect you from a certain level of storm surge, but you’ll lose your beach, right? There are risks and benefits associated with each one of the adaptation technologies you could put in place. There are a lot of options. That’s why there are issues around specificity versus generalizability. It needs to be plausible, but you don’t want to go too far into the nitty-gritty details of things. Because actually, people don’t need all the details to be able to make a logical, educated decision.

What struck me when you first started talking was the idea of moving away from problem-solving as a painful process to something fun where we can tap into our innate ability to play with things until we figure out solutions. Can you elaborate on that?

I firmly believe that crisis cannot be the only driving force behind climate action. We need to incorporate an element of fun. The crisis narrative is a powerful motivator, but it can produce a short-sighted approach to problem-solving. Yes, climate change is a pressing issue. Yes, we need to move forward with action. But it doesn’t have to always be the ambulance at the bottom of the cliff. The other issue is that you can leave people behind. We need to think about the larger systems we’re operating in and who we will be supporting and helping in the long term. [Serious] games allow people to think about that in a more big-picture, holistic way.

How does your work from this book chapter relate to UEP’s values?

When we designed each game, we constantly communicated with the people who wanted it. It was not a case where we developed the game, gave it to people, and considered the job done. Instead, it has been a collaborative process. We addressed the concerns of the communities we were trying to help and ensured that the game was implementable; this is so much of what UEP is all about. We don’t want to create these things in a box somewhere, publish a paper on it, and then be done. The work we’re trying to do here is all about creating a tool that can be used. The [game] is all open access. The code is accessible to anybody. It’s all open-access software. Everything we’ve done has been about creating seeds of change that others can take and grow elsewhere, and that’s really in line with what UEP is all about.

- A couple of links to articles on this game: the first one is a published, peer review article, the second is a more accessible magazine article.

↩︎