By Elijah Mensah

Over the summer, I worked as a research assistant with Professor Justin Hollander and Karen Jacobsen on a Tufts and Woodwell Climate Research Center funded study that provided an opportunity to visit the project site in Kampala, Uganda. Our research aim is to investigate the impact of plastic pollution in three informal settlements of Kampala with a long-term goal of supporting plastic collection and recycling efforts. I worked with other Research assistants and project co-investigator Professor Jacobsen to collect data in the first phase of the project. I would like to share key highlights from our field trip.

All about Kampala, Uganda

Uganda, also known as the “Pearl of Africa” for its beautiful scenery, is a landlocked country located on the east coast of Africa. It borders Rwanda to the southeast, DRC to the west, Kenya to the east, South Sudan to the north and Tanzania to the south. The capital city Kampala is known to be experiencing unprecedented growth with a population estimated at 3.8 million at an annual change rate of 5.31% as of 2023. The growth and expansion are visible through the mushrooming of informal settlements across the city, especially in low-lying areas. According to the UN-Habitat, over 60% of the population live in informal settlements where there is a lack of sustainable urban infrastructure leading to the demand for better quality water, sanitation facilities, electricity, roads, security and proper solid waste management systems. Kampala is known to be vulnerable to recurrent migration and climate challenges, including urban heat waves and intense rainfall that are less predictive (Lwasa, 2010). The conversion of wetlands to human settlements, high rainfalls and environmental degradation including poor solid waste management and improper physical planning are drivers for severe flooding in informal settlements (Lwasa, 2010). According to local knowledge, single-use plastics have been a prime contributor to flooding through the blocking of storm drains and other waterways. It has also played a major role in harboring mosquito larvae that cause malaria and also pose a threat to human health through burning disposal methods. As research has confirmed the impacts of plastic pollution on wildlife and the marine ecosystem, there is little information on the assessment of the detrimental effects of plastic pollution on humans, especially for those living in low-income communities.

1. Local partnerships: Our target study area is informal settlements in Greater Kampala, including Acholi Quarter, Kifumira, Najjanakumbi, and Ntinda. We started by collaborating with community organizations such as the Aliguma Foundation and UNHCR, government organizations such as the KCCA, NEMA, the Makerere University, independent research institutions, and plastic recycling companies to discuss the problem of flooding, the plastics challenge, how much work or research that has been done to date and to explore partnerships of working together to find a lasting solution.

2. Community engagement: We established strong relationships with community leaders and residents across the numerous informal settlements we visited. Our community entry received a warm welcome that allowed us to explore various challenges of the communities about flooding and single-use plastic pollution. We used the opportunity to learn about the potential solutions the communities expected from their government, businesses, and civil society.

3. Key Informant Interviews: We conducted interviews with government authorities, researchers, policymakers, community leaders, and local nonprofits to understand the problem of plastic pollution and its related impacts on flooding and public health in the informal settlements. Some questions during our interviews were informed by extensive research of literature to understand the problem further. We also delved into national and city-level policies that address plastic pollution and flooding in informal settlements to enable us to make policy recommendations.

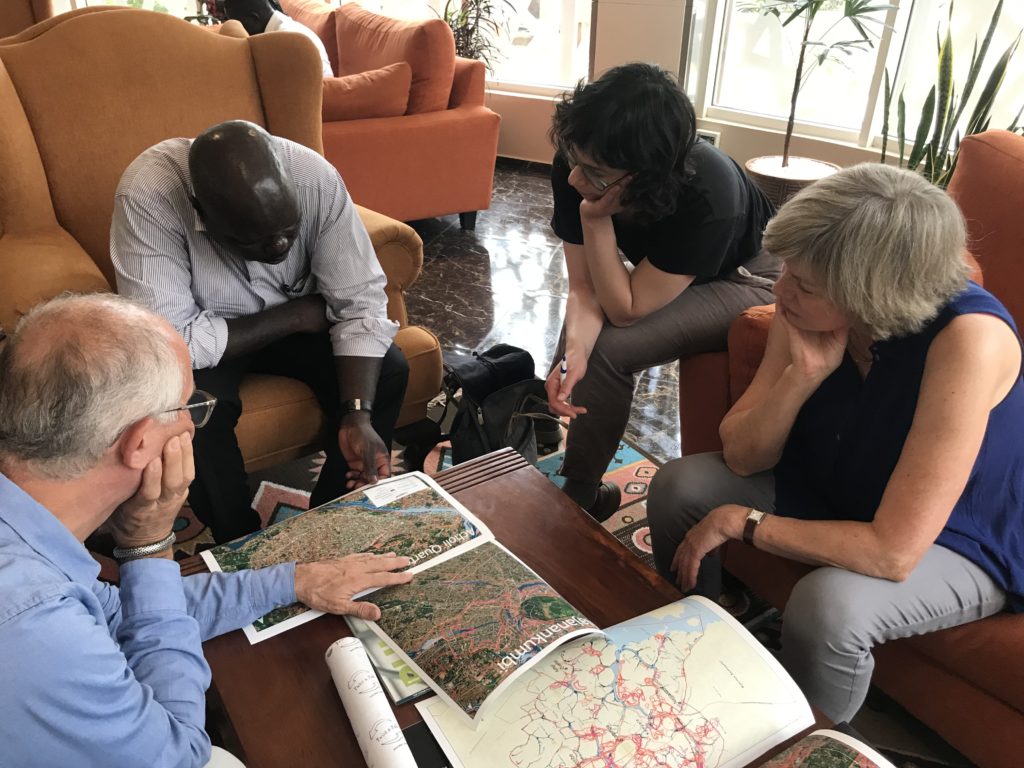

4. Spatial analysis and mapping: This project draws from a previous project done by Professor Hollander, Jacobsen, and the Woodwell Research Center to conduct advanced geo-spatial analysis that delineates the bounds of flood-prone areas, tests the spatial relationship between social and environmental vulnerability, and explores the heightened risks of plastic waste pollution and related impacts to public health and flooding in informal settlements. The research team collected spatial data and conducted ground truthing and observation using maps to understand the boundaries and the extent of change in the informal settlements.

In summary, my experience in Kampala was enriching and honed my research skills. It has also highlighted the urgent need for sustainable solutions to address the plastic pollution problem in the informal settlements of Kampala. Our findings confirm Kampala generates over 2000MT of solid waste daily, of which 1300MT is collected to the landfill and the remaining is left behind in communities due to inaccessible road network for garbage trucks or simply the inability of locals to pay for collections. It was estimated that 75% of the waste is organic, and plastics form about 12%, often not collected for recycling. The incessant littering and indiscriminate open garbage dumping was confirmed to play a significant role in aggravating flooding in informal settlements as their downstream locations serve as a reservoir for upstream run-offs from the city, therefore endangering lives and properties. We took note of government initiatives to improve education and awareness on waste management and the proposed implementation of the Extend Producer Responsibility (EPR) policy to mitigate plastic pollution. The drawback has been the slow pace of government taking action on the matter and the interference of lobbyists in the plastic manufacturing industry, specifically with a ban on the use of single-use plastics in the country.

The knowledge and insights gained from this project will be a valuable foundation for my thesis research in Kumasi, Ghana in the Fall. With funding support from the Tufts CREATE Fellowship program, I’ll be testing the hypothesis of whether single-use plastics are a significant contributor to flooding and consequent health and safety hazards in the informal settlements of the Asawase and Aboabo township and draw comparative analysis with outcomes from Kampala, Uganda. Drawing parallels between the two regions and their unique challenges will be a valuable contribution to addressing the solid waste management problem and creating a more sustainable future for informal settlements in developing countries. I want to thank Professor Hollander, Jacobsen, and the team for the opportunity to learn and contribute to this project.

Bibliography

Kampala Population 2023. Accessed September 19, 2023. https://worldpopulationreview.com/world-cities/kampala-population.

Lwasa, S. 2010. Adapting urban areas in Africa to climate change: The case of Kampala. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 2(3), 166–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2010.06.009

UN-Habitat 2006. Situation analysis of informal settlements in Kampala. https://unhabitat.org/situation-analysis-of-informal-settlements-in-kampala