On Wednesday, September 20th, Grassroots International hosted a reading and panel discussion with authors of a new book from Food First, entitled Land Justice: Re-imagining Land, Food, and the Commons in the United States. Held at the Tufts Health Sciences Campus, the event was co-sponsored in part by the Tufts Urban and Environmental Planning and Policy (UEP) program, Friedman Justice League, and Friedman Student Council. Current UEP/AFE dual degree student Kathleen Nay reflects on what she learned.

In undergrad, I had a history professor who liked to remind us that “the past is always present.” He opened each class period with a quirky anecdote tying the distant past to today—the origin of the phrase “to throw the baby out with the bathwater,” or the ancient beginnings of practices we think of as quite modern—applying makeup, for example, or playing table games. He used it as a mnemonic device to encourage students to remember the importance of history. While most of the historical snippets he shared escape me now, the idea that the roots of the past become reaching tendrils in the present is something I still think about often.

But history is not always a quirky story about babies and bathwater. For many, historical oppression manifests as inherited present-day trauma. I’ve been reminded of this throughout my time in the UEP and Friedman programs, where I’m not only learning what it means to be an expert in my field (environmental and agricultural policy), but also where I’m learning to confront my privilege… and hopefully, to be a better human being.

Last Wednesday night, around sixty people gathered to hear from the editor and coauthors of a new book from Food First, entitled Land Justice: Re-imagining Land, Food, and the Commons in the United States. In it more than 20 contributors examine themes of black agrarianism and liberation; women’s work on the land; privilege in property ownership; indigenous leadership; migration and dispossession; the implications of transnational food regimes; land-based racism; and finally, opportunities for activism and healing. The volume includes a chapter on land access, written by UEP alum Caitlin Hachmyer (MA ’13).

The evening began with a short mistica ceremony that grounded us, leading us to reflect on our relationship with the Earth and our place upon it; to honor those who have sacrificed (and are sacrificing) everything on the front lines of land justice; and to reflect on the ways in which we might continue learning and offering solidarity to those fighting for land justice. On the ground in front of us were seeds, soil, and signifiers of the struggle against capitalist interests and colonialist occupiers of contested land.

Director of Food First and coeditor of the new book, Eric Holt-Gimenez opened with a reading from the volume’s introduction, which reflects on a mythos well-known to Americans and to New Englanders in particular, wherein Squanto [Tisquantum] shows the pilgrims how to plant herring alongside corn, to nourish the crop and ensure a plentiful harvest. What the mythic Thanksgiving story fails to capture, however, is that Tisquantum was a captive of European explorers. While held in Europe for 16 years, his tribes—the Massasoit and Wampanoag peoples of the “New World”—were decimated by disease introduced by the colonists who overtook their homeland.

The story of early America doesn’t offer much more hope for agrarianism. Over the next centuries, dispossessed British, Nordic, and European peasants gradually lead the transition from agrarianism to the Industrial Revolution, and over time agriculture became less about feeding people and more about feeding the capitalist machine. Holt-Gimenez’s introduction sets the historical stage by emphasizing that “racial injustice and the stark inequities in property and wealth in the US countryside aren’t just a quirk of history, but a structural feature of capitalist agriculture… In order to succeed in building an alternative agrarian future, today’s social movements will have to dismantle those structures.” When you begin to examine—really examine—the root causes of hunger in our country, he says, it all comes back to the land. The past is always present.

But there are seeds of resistance, and their stories are told in Land Justice.

The first author to speak at Wednesday’s panel was Kirtrina Baxter, whose contribution to the book centers on black women healing through innate agrarian artistry. She introduced the concept of women as seed keepers. “Black women’s acts of creating are often relegated to carrying the seeds of the human population,” Baxter and her chapter coauthors write, but “through historical and contemporary narratives of Black women agrarians, activists, and organizers, we describe innate agrarian artistry as the creative, feminine use of land-based resistance to simultaneously preserve the people and soil.”

Suyapa Gonzalez was the next panelist to speak. Though not a contributing author, Gonzalez is an organizer with GreenRoots, a community-based organization in Chelsea, Massachusetts committed to achieving environmental justice through collective action, unity, education, and youth leadership. Through a translator, she gave a rousing appeal for land justice in Chelsea, where much of the soil is contaminated from years of chemical dumping, and where 72% of households are renter-occupied. “After God, it is to la madre Tierra that we owe our lives. If [our Mother Earth] dies, we will also die,” she opened, and ended with a call for everyone to demand better protections for the land that gives life.

The final coauthor to speak was Hartman Deetz, a member of the Mashpee-Wampanoag tribe and an activist for land justice and indigenous rights. Deetz owns two acres of Mashpee land in Cape Cod—two acres of land, he emphasized, which has perpetually been under Mashpee ownership and never owned by white people.

But the taking of indigenous land is not simply a footnote in the distant past. Here too, the past is present. Today the Mashpee-Wampanoag tribe is fighting the government for federal recognition of their tribal status and rights to retain ownership over 11,000 acres of ancestral land. Unfortunately, it’s a situation not unique to the Mashpee; in his Land Justice chapter, Deetz recounts his experience standing alongside the Standing Rock Sioux in protest of the Dakota Access Pipeline. People are still losing lives and livelihoods in the struggle for land justice.

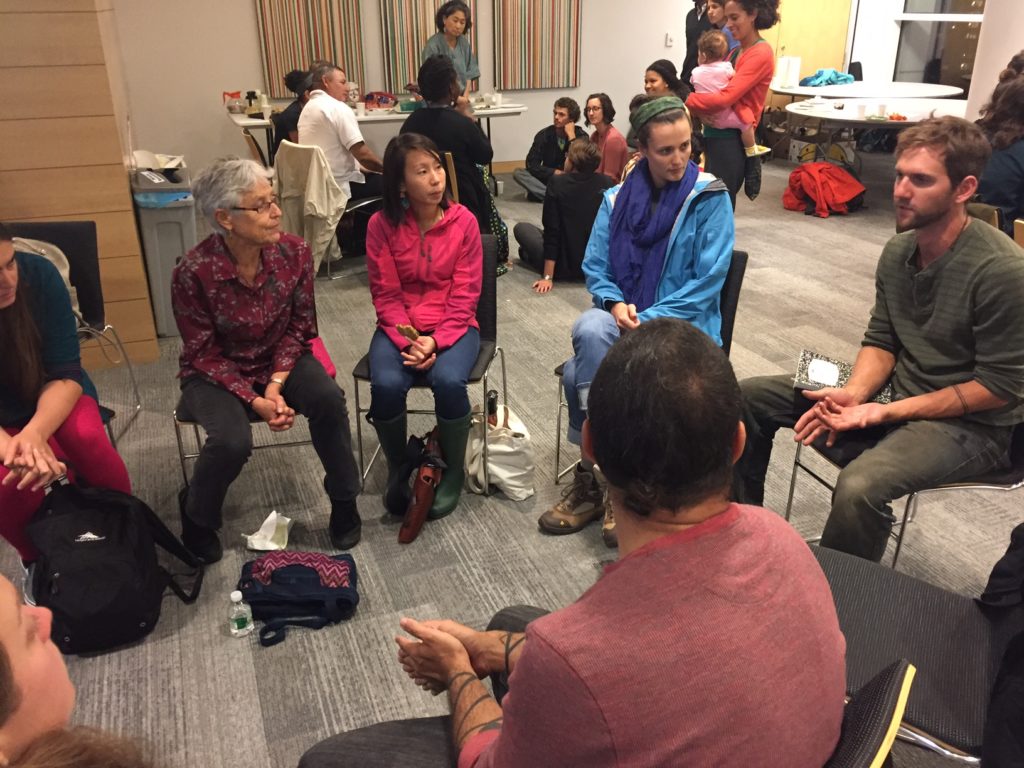

The evening closed with a chance for attendees to break into small groups for discussion and reflection. My group took the opportunity to reflect on just how present the past really is, and how the histories of indigenous peoples and people of color, so deeply tied to land ownership (or lack thereof), are all but erased in our culture. I left with a deeper resolve to seek out those hidden histories, to be more supportive of efforts for democratic community control of land in my profession and practice, and to lend my support to organizations that do the same.

Kathleen Nay is a third year UEP/AFE dual degree student. This summer she discovered Native-Land.ca, a resource to help North Americans learn more about the indigenous histories and languages of the region where they live. If you have a zip or postal code, you too can learn more about your home on native land.