Before attending UEP, I stumbled upon a blog post about Teaching Democracy, a community-university training program about popular and participatory education methods, and became intrigued. I wondered, “Is it really possible for a university to share power and leverage its resources to support movement-building?” Part of what drew me to attend Tufts was the promise of getting to explore this question first-hand.

Two years later, I found myself working on a thesis project that explored this question! My thesis research evaluated Teaching Democracy’s activities from 2016-2019. The project aimed to understand what participants learned in Teaching Democracy’s first three years about the embodied practices of democracy, as well as how the course can continue to develop in years to come.

In this project, I analyzed interviews and journal submissions from 20 respondents who attended Teaching Democracy between 2016 and 2019. As a participant in 2018 and co-facilitator in 2019, I also incorporated my own perspectives by reviewing my written reflections and conversations with other respondents. I finished this project in December 2019 and in February 2020, I had the opportunity to apply what I learned by co-facilitating Teaching Democracy with May Louie. Throughout the project, I aspired to engage in a spiral process of acting, reflecting, and theory-building, also known as ‘praxis.’

I am now working on a publication with Penn Loh and Joceline Fidalgo that explores power relationships in the wider CoResearch-CoLearning (CORE) partnership, of which Teaching Democracy is a key component. We will continue to engage in action and reflection to explore emergent questions, some of which I outline at the end of this post.

We’re all familiar with the feeling of entering an educational space and thinking, “I am here to receive knowledge.” You may even be in this mindset as you read this post. In traditional education systems, knowledge flows in one direction from the expert/teacher to the non-expert/student. This process limits the development of a learner’s critical consciousness by treating students as receptacles of knowledge rather than co-producers. Paolo Freire, a critical popular education ancestor and author of Pedagogy of the Oppressed, termed this system the “banking model” of education. It is a model that trains people to adapt—to fit better into society as it is. Unless the banking model is intentionally disrupted, those who already hold power benefit from the production of research, knowledge, and action.

Reflection moment: The banking model happens anywhere where dominant ideologies are reproduced: in high schools, universities, city planning meetings, and more spaces. Teachers wield power over students, researchers over subjects, and government officials over neighborhood residents. When have you experienced a teacher, government official, or other authority exercise power over you? How did that feel?

Popular education as a framework and set of practices turns the banking model on its head. Popular and participatory education aim to challenge hierarchical and dominant methods of learning and support leadership and critical consciousness development in progressive social movements. Popular education treats those directly impacted—with lived experience of social and economic systems—as experts about how these systems should change.

The popular education movement originated in Latin America and is intimately connected with building people power through social movements. In fact, according to historian Liam Kane, the term popular carries strong class connotations, referring to peasants and factory workers as opposed to those with more financial resources. Paolo Freire began writing about popular education in the 1950s while working on adult literacy projects in northeastern Brazil. In the 1970s and 1980s, principles of popular education continued to be adopted and radicalized by thousands of popular grassroots movements, which emerged all over Latin America (Kane, 2010). The Landless Rural Workers’ Movement in Brazil, for example, used the principles of popular education to build an autonomous school system of 1,800 schools, and offered courses for activists. Freire’s theory also deeply influenced the formation of the Highlander Center for Research and Education. Since the 1930s, under the guiding influence of Myles Horton, Highlander staff have trained a “yeasty culture” of civil rights and labor activists committed to working toward social justice and equality (Horton, 1998).

Reflection moment: When have you experienced a moment of power with? Can you think of a moment where you had more power than someone else and chose to cede power and be in solidarity with them? How did this feel? Or, alternatively, have you experienced a moment where someone with more power chose to cede this power to you? What was the impact?

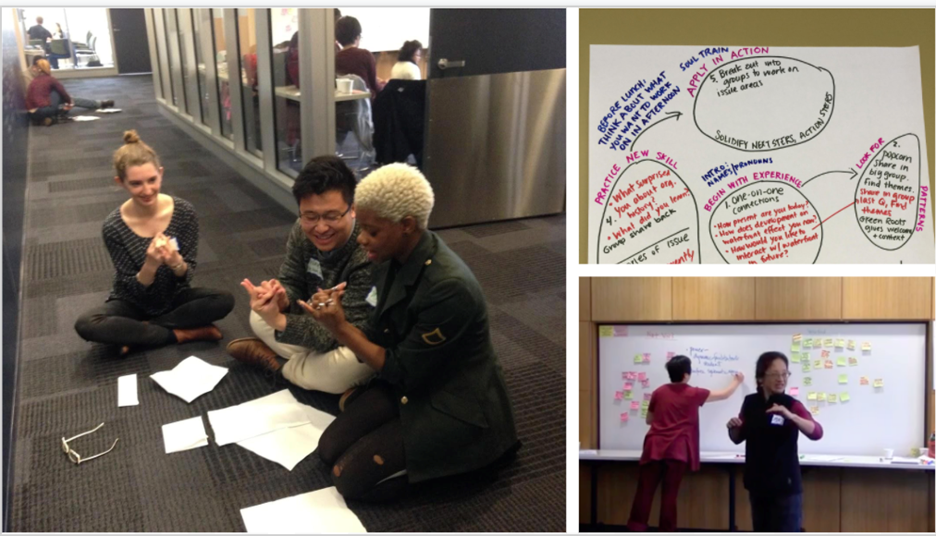

Teaching Democracy is a community-university training program that aims to introduce community organizers and Tufts students to the principles and practices of popular education with the goal of building stronger movements for social justice in Greater Boston. Penn Loh, Senior Lecturer at UEP, initiated the program with a team of community practitioners, educators, and students. May Louie, founder of the Activist Training Institute, was brought on as curriculum developer, based on her work establishing the Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative’s Resident Development Institute. This constellation of organizers and educators recognized a need for skill-building in popular education methods for community organizers in Greater Boston and for bottom-up learning at Tufts. Rather than replicating a popular education training across many community organizations, the program would train a cohort each year, and serve as a community of practice for sharing resources and knowledge. These four goals have guided Teaching Democracy’s curriculum and development each year:

- Build the capacity of students, faculty, community partners to identify and practice using popular and participatory education methods.

- Forge stronger relationships between Tufts students, faculty, and community members in Greater Boston.

- Increase the capacity of participants to use popular and participatory practices in their own social change work.

- Sustain a community of practice in person and via an online platform that holds curricular guides, videos, blog, other resources.

In 2018, I experienced Teaching Democracy firsthand as a participant. The following year, I co-facilitated Teaching Democracy with May Louie. By the end of 2019, Teaching Democracy had trained over 70 community members and students. By that point, I had already begun an evaluation project for Penn and this became my thesis research. Through the project, I hoped to learn about the micro-practices of democracy that Teaching Democracy conveyed, through exploring these research questions:

What kinds of shifts did respondents experience through participation in Teaching Democracy? How can the program continue to develop as a community-university training space?

Given the emergent and context-specific nature of the research question, I used a mixed method approach that included reviewing design team notes, facilitation modules, grant reports, respondent applications, reflective journals of 10 participants and conducting semi-structured interviews with another 10 respondents. As a participant in 2018 and co-facilitator in 2019, I also incorporated my own perspectives on the course by reviewing my own written reflections and conversations with other respondents.

Through the project, I came to understand that respondents experienced three main shifts by participating in Teaching Democracy. First, they reported greater confidence in introducing others to basic popular and participatory frameworks. Respondents also noted an increased commitment to designing sessions based on the popular education principle of “centering local knowledge,” through problem-posing and participatory techniques. Finally, respondents reported a deeper understanding of how to share and cede power as facilitators. While these shifts and practices may appear small, when collectively implemented, they begin to build more complex systems and patterns, embodying the concept of emergence (Brown, 2017).

Shift #1: Through experiential learning and written resources, respondents deepened their understanding of and ability to communicate about popular education. Participants experienced heightened confidence in introducing popular and participatory education frameworks to others and reignited their commitment to embedding these practices in their work. Participants also reported drawing on the values of popular education in their agenda design for meetings.

An organizer from Matahari Womens Workers Center, who attended the training with four other member-leaders in 2019, shared that Teaching Democracy gave language to and validated organizing and education practices Matahari already uses. A Tufts student shared that she benefited from reading theoretical literature about popular and participatory education through Teaching Democracy. Some of the key principles and practices of popular education that Teaching Democracy introduces include:

- Popular education holds a goal of building collective consciousness and action for change

- Facilitators pose problems to center the concrete experience of ordinary people

- It involves a high level of participation; everyone teaches, everyone learns

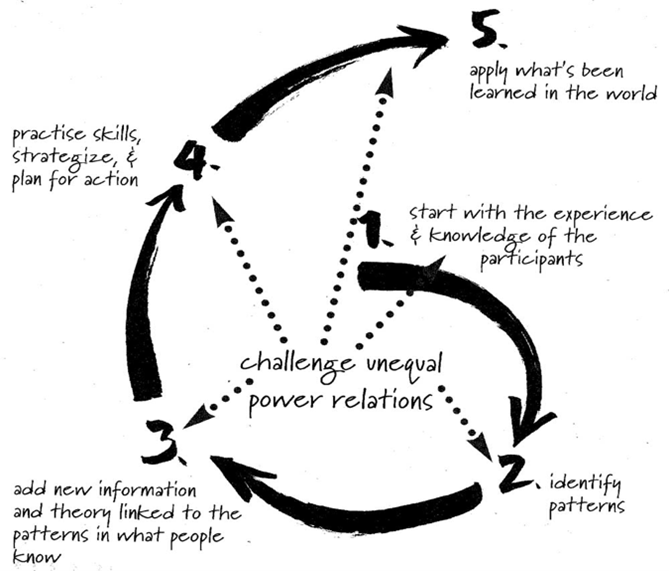

- The process of action and reflecting to transform the world is a spiral, not linear, process

- Popular education is overtly political and critical of the status quo

Shift #2: Respondents gained new skills around—and deepened their commitment to—”centering local knowledge.” Beyond communicating about the frameworks, participants reported feeling more equipped to center those most impacted in meeting spaces. This happened in two main ways. Some attendees now design sessions with a pre-determined plan of action or learning objective and build in participatory activities to support participants in feeling more connected to the goal. Other attendees now consciously design sessions that do not have a pre-supposed plan of action, but rather create space for participants to share their experiences and develop a collective agenda from there. An organizer with Dorchester Not For Sale, for example, shared that the “problem-posing” portion of Teaching Democracy supported her efforts to plan for a parent meeting. Her Teaching Democracy cohort helped her recognize her own assumptions about the parents’ experiences and develop a clear set of questions without presupposed ideas.

Shift #3: Respondents learned more about how to share power as a facilitator, as well as the challenges in doing so. Attendees reported feeling more prepared to share and cede power as a facilitator, by moving toward co-creation of agendas with participants and implementing more radical collective decision-making methods. One participant in 2018, who works at a foundation, shared that “In one Teaching Democracy activity, our audience asked us why we, acting as parents organizing in the context of Boston Public Schools, had taken on the issue of school start times, rather than addressing a deeper challenge of Black and Brown children having lower success rates. We didn’t have a way to respond to this in the moment.” Through the activity, the participant realized that while setting an agenda ahead of time is important, it needs to be flexible enough to allow new information to emerge and shift the entire direction of a meeting.

Future Areas for Reflection

There are several questions that will be worth exploring in future iterations of Teaching Democracy. Many interviewees wondered what kinds of relationships within the organizing community does Teaching Democracy aim to build? Is the purpose to strengthen bonds within or between community organizations? If so, what is the guiding strategy for building these relationships? How does building relationships between Tufts students and the Greater Boston organizing community support movement-building? How can all of these relationships continue to grow after the training?

A second series of questions relates to how power shows up in all of the shifts that participants experienced. In terms of framing, why is it important for community organizations to have language for what they are already doing? How does academic validation advance or limit power-building goals? In other words, who does the language benefit? In terms of centering local knowledge through problem-posing and participatory techniques, how can these tools be power-neutral or explicitly center those with the least access to structural power? Many interviewees expressed interest in how popular versus participatory education as frameworks deal with power differently.

Finally, interviewees expressed curiosity about how decision-making processes within popular education support power-sharing across identities with different amounts of power. Each step of this spiral model involves decision-making, and power mediates how those decisions are made. For example, who gets to decide what kind of new information and theories are added in step 3 of the spiral? How can a group create a container where it is safe for everyone to practice new skills and apply the learning in the ‘real’ world? How is the process of reflection mediated by power? How can reflection processes ensure everyone, regardless of the identities and power they hold, feels comfortable sharing their most authentic insights?

Thank you to Penn Loh, May Louie, Laurie Goldman, and interviewees from AARW, VietAid, SCC, DSNI, JALSA, Dot Not For Sale, Matahari, Tufts UEP and Tufts Diversity and Inclusion Program for your support, participation, and excitement about this project!

Works Referenced

Brown, Adrienne Maree. (2017). Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds. Chico: AK Press.

Horton, M. (1998). The Long Haul: An Autobiography. New York: Teachers College Press.

Kane, L. (2010). Community Development: Learning from Popular Education in Latin America.

Community Development, 45 (3), 276-286.