Findings: Bike Facilities Do Not Increase Housing Prices

By Phoebe Whitwell, ’24

When I was beginning the thesis process, I knew that I intended to return to MassDOT, where I had interned, and work as a transportation planner initiating and facilitating projects to construct shared use paths and other active transportation facilities. I therefore decided I needed to better understand the relationship between bicycle facilities and potential impacts on neighborhoods if I was going to start a career built around bike lanes.

Environmental activists, transportation planners, and public health officials call for more bike lanes to reduce car use, traffic congestion, and carbon footprint and to encourage active transportation. However, affordable housing advocates and local residents warn that constructing bicycle infrastructure leads to higher housing costs, gentrification, and displacement. My advisor, Prof. Shomon Shamsuddin, and I developed the following research question in an attempt to explore this debate: how does the installation of bicycle facilities in Boston relate spatially and temporally to rising housing values and changing neighborhood demographics?

Given the data we had, we were limited on how definitive our response could be. For one thing, we can only observe the statistical significance of a possible relationship between two variables, not state causation. For another, since we were tracking housing prices and not people, we couldn’t draw any conclusions about things like gentrification or displacement. Even with these limitations, it felt worthwhile to explore this topic using the methods and data I had at my disposal.

The method I chose was a panel regression model. Panel data, also known as cross-sectional time-series data, consists of data points for the same entities over time. In this project, the entities are assessed property values for City of Boston parcels. Property values are assessed and published every year by the City assessing department, so I had data points for many parcels for each year within my study period. The panel regression model both compares changes over time within each entity (each parcel, in this case) and compares entities to each other.

Using this model also allowed me to control for variables not otherwise accounted for in the analysis related to the differences between entities (entity fixed effects) and the passage of time (time fixed effects). This was critical because factors related to property values are varied, amorphous, complicated, and difficult to measure. For instance, I didn’t have any data on things like housing quality or neighborhood desirability. Those kinds of differences between parcels would be represented by the entity fixed effect variable. Similarly, the time fixed effects accounted for overall trends in property values in the area over time (as Boston residents know better than anyone, they’re increasing).

There’s no one accepted metric used to analyze bicycle facility distribution in the literature; different studies use variables focused on connectivity or accessibility to destinations, such as distance from a given point to the nearest bicycle facility. Since I was interested in bicycle facility presence, not usability, I chose to calculate my own metric of bicycle facility coverage which evaluated the percentage of roads within a half mile of each parcel which had bicycle facilities. Since I had shapefiles of Boston’s bicycle facilities for each year within my study period, I was able to calculate bicycle facility coverage for each parcel for each year and relate bicycle facility coverage to assessed property values over time.

I hypothesized that greater bicycle facility coverage would be associated with increased assessed property values and analyzed the panel regression to test this hypothesis. I expected that if my hypothesis were true, the coefficient for bicycle facility coverage would be positive and statistically significant. In the end, the panel regression resulted in a simple answer: bicycle facility coverage was not statistically significantly related to assessed property values. In fact, most of the variance within panels (change in assessed property values by parcel over time, in this case) was explained by the time fixed effects included in the model, indicating that assessed property values were primarily driven by larger regional trends related to the passage of time rather than any specific variable included in the model.

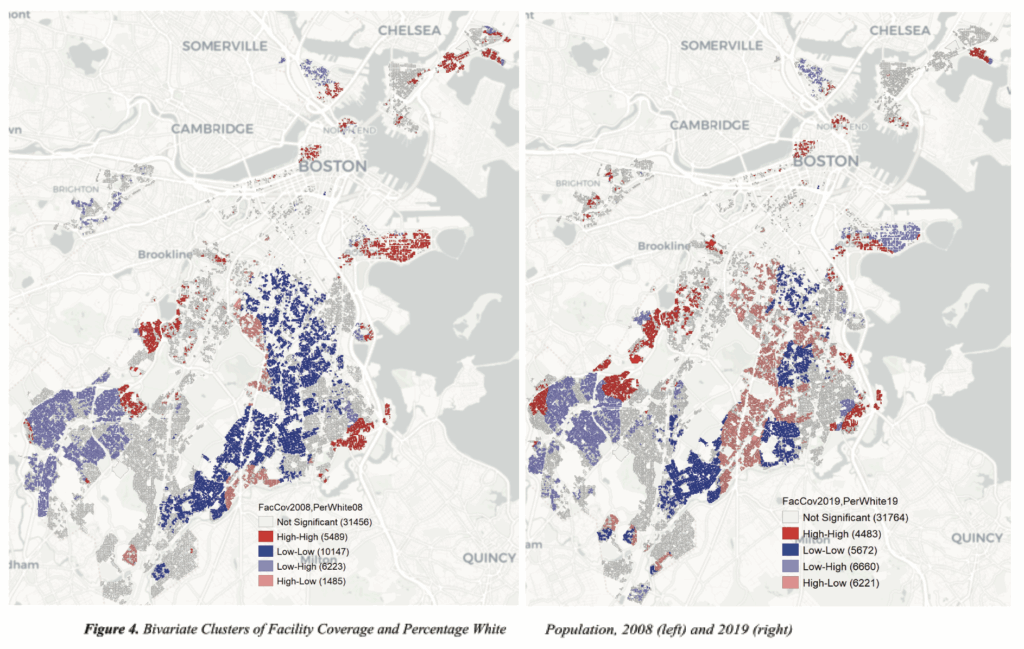

Though perhaps anticlimactic, the results of the panel regression model did offer some conclusions in the context of my wider research question. Through descriptive statistics, I observed that bicycle facility coverage steadily increased during my study period. This increase in coverage was not uniformly felt across all parcels. In 2008, Dorchester and Mattapan, both areas of the city with lower than average percentages of residents who identified as white alone, had statistically lower than average bicycle facility coverage. By 2019, focused investment in the bicycle network had greatly reduced this disparity. Though there were still pockets of lower-than-average facility coverage in these neighborhoods, for the most part, levels of facility coverage matched those in other areas of the city.

The ongoing context of gentrification in Dorchester and Mattapan is critical for interpreting the results of this analysis. There is little evidence that bicycle facilities specifically contribute to higher property values. However, as increasing property values are in large part driven by unknown regional forces, it is not possible to definitively dismiss concerns that the overall trend of greater investment in active transportation is contributing to rising housing costs across the entire metro area. Furthermore, whether or not they are correlated with bicycle facility installations, housing costs are still rising in Boston, and low-income residents are at risk of being pushed out of the city. It is entirely possible that the proposed bicycle facility expansions will end up serving mostly higher-income and white people due to larger ongoing patterns of displacement, even if the network expansion is not a specific cause.

It is therefore essential that city planners and policy makers take care to involve community members in developing hyper-local plans for bicycle facility expansion rather than solely relying on overarching goals, and that they collaborate with efforts to combat larger trends of gentrification. Engaging both community members who are enthusiastic and those with concerns will strengthen the overall implementation of the network expansion by more precisely responding to community needs. Additionally, transportation officials should support the city’s efforts to stabilize low-cost housing options and address issues of displacement and extreme housing cost burdens. Policies focused on addressing one area of inequity cannot succeed in their goals without being placed in the context of the larger system.

If the City of Boston follows this recommendation, there is good cause to be cautiously optimistic. The work done on the bicycle network expansion so far has greatly increased the equity of the network distribution and thus far has not been shown to directly contribute to gentrification. Transportation officials can continue working to make low-stress biking accessible in all areas of the city with a reasonable degree of confidence that they are not doing unintended harm. Bicycle lanes are an important tool for environmental and transportation justice. By placing this tool within a larger strategy of equity-oriented planning policies, the City of Boston can ensure that they will truly serve cyclists of all ages, abilities, and backgrounds.

Read the full Masters Thesis, Old Streets New Bike Lanes: Bicycle Facilities and Neighborhood Change in Boston, MA, HERE.

Find Theses Honorable Mentions, Nominees, and winners from past years at the UEP Exemplary Thesis Library.